Using data to improve communications for COVID-19 in Malaysia

WHO is using the Communication for Health (C4H) approach to ensure the voice of the community is reflected in the COVID-19 response

One of the many challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic is communication, in particular, ensuring people everywhere have the most up-to-date and accurate information on how to stay safe.

Malaysia has a rich and diverse population. Beyond the major ethnic groups of Malay, indigenous Orang Asli, Chinese and Indian, many people in Malaysia come from other countries seeking a better future. While the diversity of backgrounds, languages and beliefs contributes to the county's vibrant culture, it also presents challenges in communicating public health advice and ensuring that everyone is informed and empowered to take actions that will protect their health.

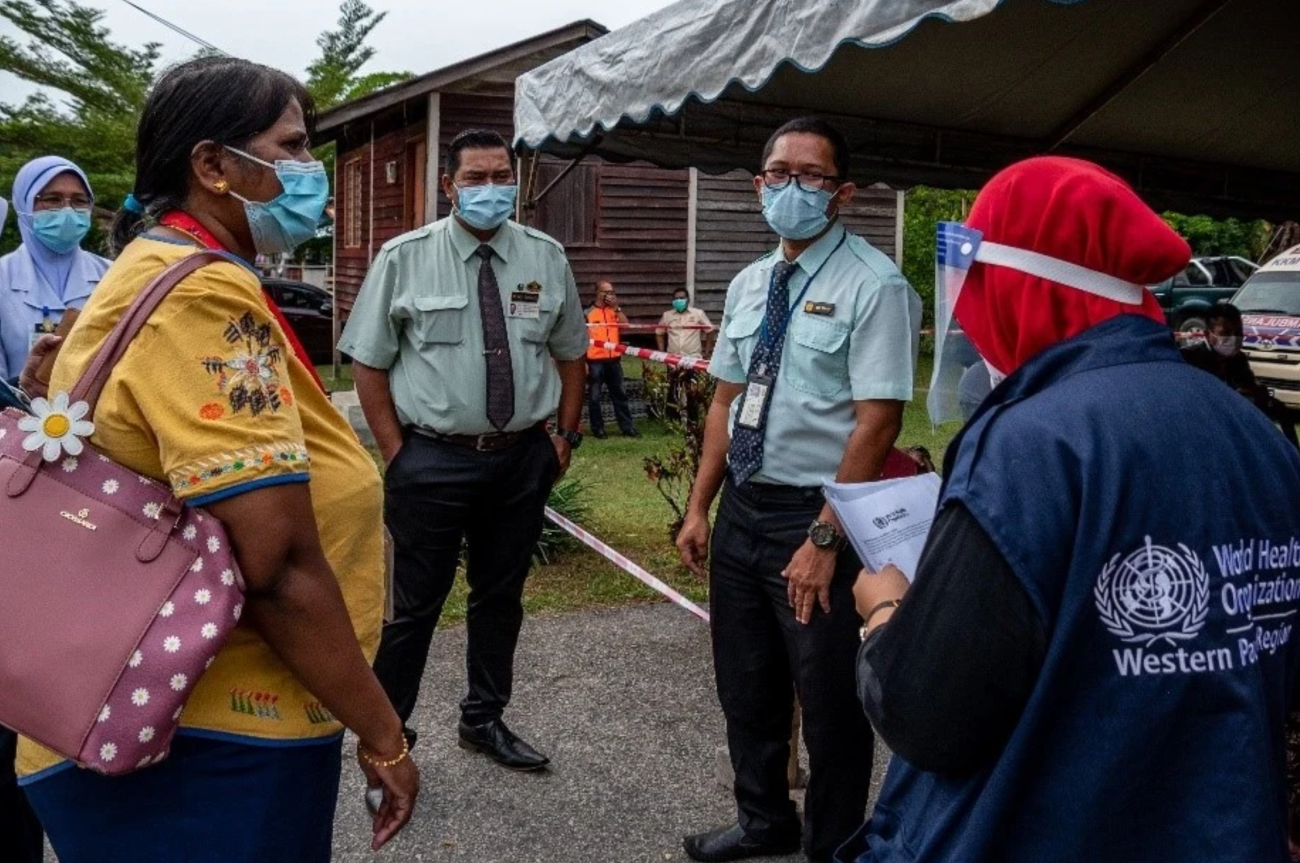

WHO is working with the Ministry of Health and partners in Malaysia to apply the Communication for Health (C4H) approach, establishing two-way communication channels with communities and drawing on data to ensure that the thoughts, feelings and behaviours of everyone in Malaysia are at the centre of communication efforts.

C4H leverages the power of communication as a tool for health. It refers to behaviourally informed and evidence-based communications, using insights from data collection to target the messaging to groups based on their needs and preferences.

The Honourable YB Khairy Jamaluddin, Minister of Health in Malaysia, is a strong advocate of strategic communications. “Communication is a public health intervention and it is a technical public health discipline,” said Minister Jamaluddin.

In line with the approach, WHO and health authorities in Malaysia conducted surveys and focus group discussions to identify knowledge gaps, respond to rumours and understand community perceptions and behaviours.

In mid-2020, survey results revealed that COVID-19 was not perceived as a severe disease by nearly 80% of respondents, especially among youth and young working adults. In response, the Ministry of Health and WHO developed an inclusive strategy and campaign for youth. One component was the “Be a Superhero, Wear a Mask” campaign that generated millions of views on social media in Malaysia and across the globe. Another important part of this work involved collaborating with local and international institutions to crowdsource solutions for an engaged and risk-informed youth population.

The WHO Representative for Malaysia, Brunei Darussalam and Singapore, Dr Lo Ying-Ru Jaqueline, highlighted the importance of setting up two-way mechanisms for dialogue.

“We engaged with local civil society organizations to work directly with communities, going door to door not just to ask questions, but to provide answers as well,” said Dr Lo.

“By tracking different social media conversational trends and topics, we also found that people tended to blame specific groups for spreading COVID-19. We then engaged with national counterparts and United Nations agencies to battle this stigma and discrimination with focused activities and messages. This included the ‘We are in this together’ campaign launched with prominent public figures, religious leaders and heads of different United Nations organizations, to promote kindness and equality,” said Dr Lo.

In response to increased fear and anxiety in the community, WHO, other United Nations agencies, nongovernmental, civil society organizations and health authorities worked together to set up hotlines and provide mental health and psychosocial support to COVID-19 patients and the public. Additionally, people identified religious and spiritual leaders as a key source of support, so WHO supported government collaboration with faith-based organizations to provide guidance on safely celebrating important holidays and keeping up with traditions and social events.

With the availability of vaccines, WHO worked with national counterparts, researchers and social scientists in Malaysia to set up a rumour and misinformation alert system that would allow quick and proactive response to false information in the public domain. As well as this, data had to be communicated to the public in ways that people could understand, remember and take action on.

“Data speaks to the brain, but it does not speak to the heart. We have to distill data in ways that speak to the heart,” said Minister Jamaluddin.

Through focus group discussions and key informant interviews, WHO and health authorities identified knowledge gaps and developed tailored information materials, which were translated into multiple languages to ensure that all communities had equal access to information about vaccines.

“We have a large migrant population in Malaysia – people who come to Malaysia to work. We made vaccination information and material in more than 20 languages, because if you cannot speak to people about something as personal as putting something in their body, you are not going to succeed,” said Minister Jamaluddin.

Collecting and triangulating data is helping WHO and the Ministry of Health in Malaysia understand what is important to people. Information continues to be turned into actionable intelligence, creating more targeted strategies that address concerns and provide the knowledge and resources people need to make informed decisions about their health.

Dr Lo said, “We continue to listen, learn, and base decision-making on evidence while treating the data not just as numbers, but as people with valid concerns, questions and ideas.”