Ensuring universal access to Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights and adapting service delivery during COVID-19 to eliminate violence against women

by Dr Fatima Ghani, Ms Tengku Aira Tengku Razif, and Dato Dr Narimah Awin

For years, Nurul* has lived in fear of her abusive husband. What started as psychological abuse escalated to more serious physical violence during the COVID-19-related movement restrictions that made her fear for her life and that of her 3-year-old son. She felt economically dependent and alone, and did not know what help was available for someone in her situation or how to seek it safely.

Stories like Nurul’s are not uncommon in Malaysia. However, gender-based violence (GBV) is underreported due to stigma, fear of retribution, and misperceptions by the police and other service providers – including many women themselves and families – that domestic violence is a private matter, resulting in inadequate protection for women. Violent cases reported to the Malaysian authorities represent the tip of the iceberg, which often results in impunity for perpetrators of violence, perpetuating a culture of tolerance for violence.

Both the risk of GBV and barriers to access support services increase during health emergencies

Helplines for both the NGO Women’s Aid Organisation (WAO) and the Malaysia Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development (MWFCD, Talian Kasih Helpline) reported significant increases in distress calls and messages since the nation-wide lockdown in March 2020, compared to pre-pandemic levels.

Ensuring access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights (SRHR) essential services such as lifesaving support for GBV survivors requires particular attention during health emergencies. As in most countries, COVID-19 related movement restrictions in Malaysia disrupted livelihoods, exacerbated socioeconomic and gender inequalities, and added accessibility barriers to SRHR services. Early efforts prioritised the treatment and containment of COVID-19, with hospitals and community clinics limiting or halting routine SRHR services. Due to disrupted access to contraception, an increase in unintended pregnancies, unsafe abortions and baby abandonments is projected, particularly among the unmarried and urban poor.

“Ensuring access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights (SRHR) essential services such as lifesaving support for GBV survivors requires particular attention during health emergencies.”

Women are families’ primary caregivers, and they face additional burdens of domestic and unpaid care work during school closures. They also constitute a big proportion of essential service providers in the response to COVID-19 (nurses, caregivers – both formal and informal – of children and the aged, teachers, domestic helpers, and cleaners). SRHR services are essential and should operate during health emergencies, and these women need support in these roles. The “Impact of COVID-19 on Reproductive Health Options” tool can help in predicting and addressing increased demand for SRH services such as contraceptive needs during service disruptions.

Lifesaving support for GBV survivors continued operating during the lockdowns via One-Stop Crisis Centres within government hospitals, although survivors might have not known about this, or were afraid of either being stopped by the police enforcing movement restrictions or being exposed to COVID-19 in the hospital. SRHR services need to be adapted within the context of COVID-19 movement restrictions to ensure they reach the most vulnerable women and girls.

Eliminating violence to accelerate the Sustainable Development Goals

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development recognises gender equality and women’s empowerment as a standalone goal that must be achieved in its own right, as well as an accelerator that will enable and contribute to the achievement of the other Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). SDG 5 aims to provide women and girls everywhere equal rights and opportunities, including living free of violence and discrimination. Sustainable development has been at the heart of Malaysia’s public policy since the 1970s.

Economic advancement in Malaysia occurred alongside the development of a universal and comprehensive health system, significantly reducing maternal and child mortality, and increasing life expectancy. Malaysia is committed to the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) Programme of Action and the Sustainable Development Agenda, which facilitated the integration of Sexual Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) services (e.g. perinatal care) into universal health coverage (UHC). However, religion remains a key influence in the enactment of SRHR, requiring innovative strategies to accommodate socio-cultural norms, beliefs and behaviours to deliver more sensitive services, such as safe abortion.

In particular, GBV is a gross violation of human rights and a serious barrier to community development. Worldwide, one in three women experience either physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetime, most commonly from their partners. Rooted in discriminatory gender norms and laws implying that women have less value and fewer rights and resulting in impunity, GBV occurs as a means of control, subjugation and exploitation that further reinforces gender inequality. It not only affects women, but also their families and communities, and incurs health, welfare, legal and economic costs and jeopardises the achievement of the SDGs.

Malaysia’s progress in addressing GBV

UN in Malaysia and the Women’s Institute of Management convened on 25 November 2019 (the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women) a meeting of survivors of violence, academia, NGOs, service providers, the government, and the public. This meeting was part of the United Nations University – International Institute for Global Health’s (UNU-IIGH) Gender and Health series and provided the forum to discuss a way forward to accelerate the SDGs, particularly SDG 5 (gender equality).

The progress made by the Malaysian government towards eliminating GBV was noted at the event, including the enforcement of the 1994 Domestic Violence Act, which was enacted in 1994. The more recently developed national roadmap for the well-being of children, as well as a sexual offender registry were also noted. The One Stop Crisis Centres established by the Ministry of Health within the Emergency Departments of public hospitals also provide a range of integrated health, welfare, and legal services to respond to GBV and child abuse. This successful model has been replicated in other low- and middle-income countries in the region.

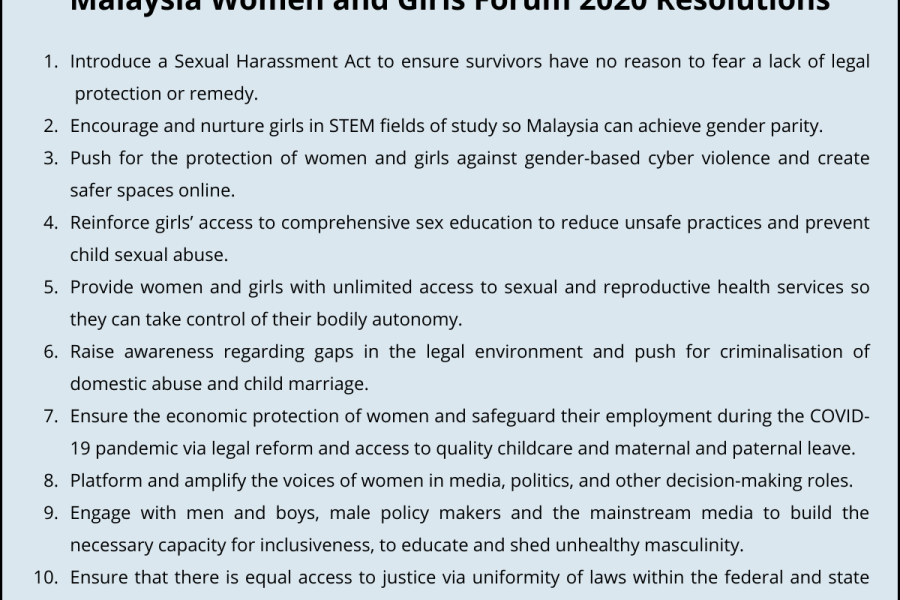

On 17th December 2020, the UN in Malaysia led by UNFPA, and in collaboration with UNU-IIGH, convened the Malaysia Women and Girls Forum (MWGF). The annual MWGF convenes multisectoral stakeholders involved in the social and economic advancement of Malaysia’s women and girls to track and provide proactive recommendations for advancing their rights and wellbeing. The 2020 Forum identified, engaged, and tracked key social, economic, and legislative changes needed to accelerate the rights and well-being of Malaysia’s women and girls.

Malaysia can accelerate the achievement of the SDGs by acting on the following recommendations.

As the Malaysian Government and NGOs adapt SRHR services delivery to ensure provision and continuity such as via digital platforms, there are some key considerations as described below.

SRHR services, particularly GBV services, should be provided in an integrated manner into national preparedness and response plans for COVID-19, including targeted financial assistance programmes. GBV services should be strengthened to address spikes during lockdowns.

A guidance document on How to create a gender-responsive pandemic plan was produced by the gender and COVID-19 working group to help decision makers address gender disparities in pandemic preparedness, response, and recovery plans, and can be adapted to suit specific contexts and resources.

The multisectoral response and recovery planning should incorporate civil society and NGOs working directly with survivors. NGOs such as WAO have played a major role in providing support for survivors and advocating for: establishing early warning systems; adequately staffed helplines; publicising helplines widely and regularly; digitalising the application and issuance of protection orders; updating referral pathways; and incorporating shelters as essential services.

WAO is collaborating with the government in developing and publicising guidelines for movement restrictions exemptions for GBV survivors to obtain protection orders. With its primary shelter at capacity, WAO is establishing a temporary emergency shelter to address GBV survivors’ needs. The MWFCD recently committed to establishing shelters for survivors as recommended by WAO, with pilot projects in hotspot states Selangor and Johor. Meanwhile, temporary shelters in hotels or hostels could be established in partnership with the private sector.

Addressing gender inequalities and GBV through legislative action

Legal system reforms are needed to secure the human rights of women (including transgender women), and to ensure the prosecution of perpetrators of violence. Suggested legal reforms for making perpetrators accountable in Malaysia include recognising Intimate Partner Violence, and amending the Domestic Violence Act to include protecting unmarried individuals in intimate partnerships, and enacting the Sexual Harassment Bill.

Child marriage, female genital mutilation (including female circumcision), emotional violence, polygamy, and marital rape are forms of GBV frequently considered a private issue, and therefore not criminalised within civil and Islamic legal systems. These harmful practices, which imply that women and girls have less value and fewer rights than men, reinforce men’s control over women and condone GBV, and should be criminalised with zero tolerance.

Additionally, discriminatory laws against the LGBTQI+ community should be identified and abolished to address the extensive transphobia in Malaysia and abuse of their human rights, which have resulted in indignity, harassment, and extreme violence leading to murders.

Health system strengthening including specialised training for service providers

It is estimated that 1 in 5 women treated in clinics have experienced domestic violence in the last year, with doctors often failing to identify early signs of abuse attributed to inadequate training, lack of primary prevention focus, and prejudices towards domestic violence as a ‘family matter’ which should not be interfered with, perpetuating GBV.

Since primary healthcare providers play a crucial role by providing a safe environment conducive to disclosure of violence, they should be appropriately trained in early detection and referral of victims of abuse.

Strengthening the health system in its functions of leadership and governance, health service delivery, preventing and managing GBV, and information systems, including confidential data collection, are key to inform effective policymaking. An integrated survivor-centred approach to service provision, including the health, social services, police and justice sectors, as is being adopted by the OSCC, should be maintained and enhanced. This approach is also suggested by the Essential Services Package for Women and Girls Subject to Violence, which provides guidelines for relevant coordination and governance mechanisms.

Educating boys and girls and men and women in non-violent conflict resolution and transforming existing harmful gender norms, attitudes, and behaviours.

Evidence-based educational interventions and campaigns to prevent interpersonal violence should be applied both at the family level and across different settings, including schools, workplaces, and government institutions to raise awareness that GBV is a matter that concerns everyone and should not be tolerated, and survivors should be encouraged to safely speak up and be supported through integrated services and referrals.

Allocating investments to prevent and address GBV through a multisectoral participatory approach.

Implementing gender responsive budgeting within government budget cycles would accelerate the achievement of the SDGs. Investment in preventing and responding to GBV saves costs, in addition to averting suffering and trauma, morbidity and mortality. Implementing the above recommendations requires political commitment and the allocation of funds to the listed activities as part of a comprehensive National Strategy to address GBV at the national, regional, and local levels. The focus has been on responding to GBV through One Stop Crisis Centres. However, investment in preventive and protective services for GBV remain largely limited. Welfare service provision for survivors relies heavily on NGOs, such as WAO, which provides limited shelters and safe spaces. Policy makers should invest on improving data collection and monitoring of GBV to inform the design, implementation and evaluation of appropriate contextual prevention and response interventions aimed at eliminating GBV, and actively engage survivors, service providers and NGOs working in this space for a more significant impact in transforming existing harmful gender dynamics.

Achieving the SDG targets

International frameworks such as CEDAW, the Beijing World Conference on Women, ICPD and the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court have resulted in some progress towards the elimination of GBV worldwide by increasing legal accountability for human rights violations, protection of the rights of women, and gender equality. Malaysia has committed to UNFPA’s strategy of achieving three zeros by 2030: 1) on an unmet need for contraception; 2) on preventable maternal deaths; and 3) on GBV and harmful practices, such as child marriage and female genital mutilation. While interventions and strategies are either in place (zero 2), or have been initiated (zero 3), more effort is required to address an unmet need for contraception.

With a decade remaining to meet the 2030 SDG targets, it is vital that Malaysia honours its international commitments by accelerating the elimination of GBV. A multisectoral strategy implemented across all levels of government with sustainable funding and including the voices of survivors and those who are supporting them, would ensure a meaningful impact in eliminating GBV and achieving the SDGs.

Dr Fatima Ghani is a researcher at the United Nations University, International Institute for Global Health.

Ms Tengku Aira Tengku Razif is a Programme Analyst with UNFPA Malaysia.

Dato Dr Narimah Awin is a Sexual and Reproductive Health Consultant for UNFPA Malaysia and former Director of Family Health Development, Ministry of Health (MoH) Malaysia.

* Name changed to protect identity of person